Father Jimmy, Billy Tom and the Antigonish Movement

By Peggy Feltmate

(This article first appeared in “Early Canadian Life” Vol 4, No 9, September 1980)

The men of St. Francis Xavier University have gone among the poor. They have planted the seeds of education and co-operation in the lives of thousands of people, irrespective of race or creed. As a man professing the Protestant faith, I make that statement, knowing it to be absolute fact. The courage that enables me to state it was given me by St. F.X.U. Nothing warms the human heart like a helping hand.

William T. Feltmate, 1938

Whitehead, Guysborough County, Nova Scotia

The Feltmate family c.1932: Front L to R: children Lindsay, Jamie, Marion. Back L to R: mother Eunice Leannas Feltmate, Billy Tom, wife Margaret and son Carroll.

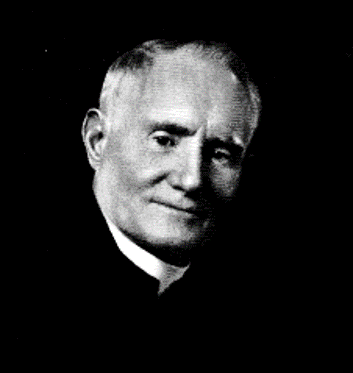

In Canada today it is difficult to visualize conditions in poorer countries. But 50 years ago, Canada too suffered crippling poverty and illiteracy. These conditions fired the vision of two Cape Breton priests, Father Jimmy Tompkins and Father Moses Coady, who were teaching at St. Francis Xavier University in the town of Antigonish 160 km northeast of Halifax. Together they moved and shook the fishermen, farmers and coal miners of Nova Scotia to become masters of their own economic destiny. My grandfather, William T. Feltmate, with his Protestant upbringing and his grade five education, was one of the coastal lamps lit by the fire of Tompkins and Coady. This is how it happened.

Father Jimmy Tompkins was from the rural community of Margaree, In the early 1900s, on faculty at St. F.X., he taught Latin by mail to his cousin Moses Coady who was still back home in Cape Breton. He was astonishingly successful in that pursuit, as he was in raising much-needed funds for expansions at the University. From travels abroad he became intensely interested in the principles of adult education, and began applying these principles at home. As Vice President of St. F.X. he first improved the faculty, (cousin Moses was now Dr. M. Coady and was one of the new members), and then began peppering publications with articles and asking experts in farm science, biology and education for advice. By 1919 he was developing the People’s School, and in 1921, a two-month course was offered. Fifty-one men, aged 17 to 57 years, attended from surrounding communities.

There was not entrance test and no fee. Volunteers taught 12 subjects ranging from Public Speaking and economics to Chemistry and Veterinary Hygiene. Dr. Coady taught Arithmetic. Father Jimmy insisted this adult education program should remain as informal as possible: “Take it with your soup…in the lobster shanty, in the boats,” he said. He was afraid the university structure might become an ivory tower, out of touch with the needs of the area. His dream was to have education taken out to the people.

Suddenly in 1922, that dream was put squarely into his own hands: his bishop gave him the parish of Canso – remote at the mouth of Chedabucto Bay, fog-ridden and extremely poor. He had never considered this eventuality. At the university he had worked to build, he had been in a milieu where writing, publishing and intellectually stimulating conferences brought results, and now he had to leave that arena – or so he thought. As it turned out, he fashioned a new arena among the nail kegs and salt barrels of the Eastern Shore.

On that shore in the small Guysborough County community of Whitehead , not far from Canso, William Thomas Feltmate was born in 1876. Known locally as Billy Tom, he fished there all his life, just as had his father, grandfather and great grandfather. He often spoke of his early education, or lack of it:

In about 1892 I left the old school house, its old wooden benches and its bare walls, with only a fifth-grade education. As soon as a boy was big enough to row an oar, he was taken from the school house and put in the bow of the boat. I remember very distinctly the day Dad told me I was big enough to go fishing, and I am going to tell you, when a boy’s Dad says he’s big enough to go fishing, he certainly feels big enough. I felt so good about it, I asked Dad if I could chew tobacco!

In his early days of fishing, (still the days of sail), the catch was traded, not sold for cash. In the fall, a vessel came in from Prince Edward Island laden with turnips, potatoes and other goods which were distributed and charged by the fish merchants until spring when the fisherman could pay for them with fish. Few people dried or salted their own fish, but rather traded it fresh with the merchants or processors who sold it in Halifax from where it was sold to the markets. But Billy Tom was a bit different even then. He didn’t give his first catch for trade, instead he sold to a merchant for cash ($3.25!) and bought himself an accordion.

Gradually sails changed to gasoline engines and trade changed to a money-based system. In spite of this progress fishermen ran into debt they hoped to be able to cover once fishing began again. The merchants and processors, however, set the fish prices. In the 1920s they were paying the fisherman 7 cents a pound for lobster and then selling at 22 cents. Exploitation was rampant as these same merchants charged artificially high prices for the gear needed to outfit for fishing. By keeping the fisherman in debt, they were assured of a steady supply of fish in season. It was this kind of situation that greeted Father Jimmy on his arrival.

As well as Canso parish, Father Jimmy had two mission churches, at Queensport and Dover. On his first visit to Dover, a tiny fishing village strewn among the boulders between Canso and Whitehead, he saw poverty, ignorance and undernourishment that resulted in crime and an all-pervasive apathy. Instead of preaching a sermon that day, he said, “Let’s talk about your problems and see what can be done.” This was something no other priest or minister had ever done before, and from then on, talk they did. Driving along the muddy back-roads, a honk of his horn would gather a group, and he would tell them about the latest news on poultry feeding, or the economic value of education, or methods of co-operation. Incredibly he managed to keep up-to-date on happenings throughout the world, and things were socially astir: the Co-operative Union of Canada had just been organized; credit unions were of increasing interest; the American Association of Adult Education was formed. Father Jimmy was invited to a meeting of the Carnegie Corporation in New York City to discuss Adult Education. He was the only Canadian there.

Back in Canso, July 1, 1927 was a sad-looking jubilee day. Father Jimmy instigated an impromptu meeting at the community hall that evening. From that meeting, a petition was sent to the government describing the plight of the people. Representatives arrived from Ottawa, and the press came from Halifax. Surprisingly, the press sided with the fishermen! The people took courage; perhaps something could be done!

And indeed in 1928, a Royal Commission was set up, and the report called for a separate Department of Fisheries. A small grant was given to organize the fishermen so that they might have a voice in decision –making. The government put a collection service on the Guysborough Shore to carry lobsters to Boston and got the Boston market price for the fishermen instead of just for the middle men. At Antigonish, St. F.X. set up its extension department under the directorship of Dr. Moses Coady.

That year also marked the first stirrings of organization in Whitehead. At the Rural and Industrial Conference held in Antigonish in 1937, Billy Tom spoke about “The Fifty-Cent Year”:

To explain the condition of things that existed previous to our organizing, I must take you back to 1928, a year that will be remembered in White Head as the “Fifty-Cent Year” because every kind of fish we produced sold for only fifty cents a hundred pounds. Cod was fifty, mackerel was fifty, haddock was fifty, and herring was fifty! But if one of us got in to Antigonish or Guysborough where there was a restaurant, dinner was fifty cents too! So 1928 well deserved to be called the “fifty-cent year.” Nevertheless, we have reason to be proud of that old 1928! For that was the turning point for the majority of fishermen in White Head. We were pressed so hard against the wall that year that it was impossible to get any closer. We were paying 70 cents a pound for twine to knot lobster trap heads and nets, $7.50 per thousand for laths for the traps. But we were getting only 7 cents per pound for market lobsters and 3 cents for small ones. It was impossible to eke out an existence.

Now we had an idea that lobsters must be selling at a good price in Boston. But how could we ship lobsters, even if the government had subsidized the boat? The local packer was using her. And we as fishermen didn’t even know how to ship a crate of lobsters; we didn’t even know the name of a man in Boston to whom we could ship. And we were so used to being skinned we were even afraid to try one crate.

But finally, after talking the matter over a great many times, we decided to try a crate among the four of us. We said that if 140 pounds of large lobsters make a crate, at 7¢ per pound it was $9.80 among the four – and if we lost it, why that was our hard luck! You see, God almighty knows everything and when He made the fisherman He knew that there was a certain class of people out to skin him. So He took precautions and ordered it so that when one skin was pulled off him another grew on. And it is a good thing that He did, or 90% of the fishermen today would be walking around skinless!

All right, we got a buyer’s name in Boston out of the “Fishing Gazette”, and we shipped our crate to him. Every evening we met, the 4 shareholders of the crate of lobsters, and talked the matter over. Some said if we could get only $15 it would be much better to ship to Boston. Another said, ‘I don’t ever expect to hear tell of them.” That poor fellow had been skinned twice in one year.

Finally one morning, after returning from hauling my traps, the wife met me at the gate and says, “There’s a great big envelope come this morning with a picture of a lobster on it.” I had never got a cheque for lobsters before and I didn’t know which end of the envelope to open. I was afraid if I opened the wrong end I might spoil the cheque. But one of the other fellows said, “Let us know the worst – Tear it open.” I tore the end of the envelope open. I don’t know how it happened; never will know; but I struck the right end. There was a cheque for $32!

I don’t think I’ll ever forget the feeling that came over me. I thought the fellow at Boston had made a mistake. One fellow suggested I’d better send the cheque back. As soon as the news got around that we had received $32 for one crate of lobsters, the trouble started. The packers held a meeting and told us that they wouldn’t buy the small lobsters if we shipped the large market ones. All right, we got together, and figured up what we had gained. And then we told the packers to keep off the grass.

So we organized in what is called a Fisherman’s Co-op. Three months after organizing, we brought the price of twine down from 70¢ to 37¢; laths from $7.50 to $3.50 a thousand; gasoline from 40¢ to 26½ ¢. That’s what organization did for us.

There were similar stories in villages all along the shore. Parish priests and local leaders like Billy Tom were catching like tinder the spark of Father Jimmy Tompkins. In the Catholic community of Port Felix, four miles from Whitehead, the fishermen studied the priniciples of co-operation and, raising $85, started a co-op store in the face of great opposition. At the end of the first year, the business had grossed $5,600. Father Jimmy was busily bringing special visitors and experts into the area.

He travelled to western Canada to observe the co-operative practices there. He wrote, he spoke, he bustled from village to village encouraging, for example the start of mink or fox farms to augment off-season income. Pigs were brought into Whitehead and Father Jimmy arranged to have a special cargo of goats flown from British Columbia and transported to Dover to provide milk for the families. The people of that community cut timber in the woods and built a little canning plant. Starting with $128, saved in ten-cent pieces over the previous two years, they bought used equipment. By the end of their first season, all the loans were paid off. They called themselves the Blue Ribbon Canners. All of these local units now federated under the umbrella organization , United Maritime Fishermen. Dr. Moses Coady had been appointed by the federal government to organize the many small villages.

In 1934, Father Jimmy returned to Antigonish for a much-needed rest, and from there, was transferred to the coal-mining town of Reserve Mines, Cape Breton. His impetus had been so strong the momentum continued to carry the Antigonish Movement forward. An important aspect of the Movement was education. The people had to learn how to manage their new stores and plants and credit unions. Thus study clubs flourished.

In Whitehead, a Boys’ Study Club was formed in 1934 and a Girls’ Study Club the following year. Billy Tom’s daughter Marion was Vice President of the Girls’ Study Club and her diaries tell us that they met at one another’s houses once a week and raised bits of money with dances and pie socials and presented variety nights perhaps featuring lantern slides of Saskatchewan, or music and skits, or a play highlighting some aspect of co-operation.

Billy Tom’s son, Jamie (my father), was the secretary for the Boys’ Study Club. The 27 members rented the church hall at ten cents per member. Articles were read aloud and discussion followed that covered co-operation and exploitation, capitalism and socialism, the menace of communism and fascism, necessities and luxuries, peace and war. A rally was organized, to be held in Port Felix, and activities slated included a mock trial, step dancing by Harry Phalen and a poem called Enthusiasm to be recited by Joe Munroe.

Billy Tom was now a regular speaker at meetings all along the shore, as well as at the annual conferences. He spoke eloquently of the need being filled by study clubs:

In 1928 one crate of lobsters set Whitehead scratching its collective head. And the more it scratched, the more it realized that it had a lot to learn and until it did learn, it would remain a village of helpless, hopeless fishermen. Then we were told that adults could educate themselves. I attended quite a number of talks on adult education given by speakers from St. F.X. One night in Port Felix, one of them went so far as to offer a wager that he could teach any man or woman in three hours to read and write his own name. I had a desire to take up that wager and from that day on I have been studying. A man or woman without some education today is like a man with his hands tied and thrown into the river. When I look back into the past I remember my old Dad. Out of twenty-six letters of the alphabet, he knew only three – his initials. He used them on is buoys and on the end corks of his nets. For forty years he piled his fish on the local fish dealer’s wharf. He never had the opportunity of finning the cost of 120 pounds of fish at 60 cents per hundred. And I regret to say that even today (1937) I can name ten or twelve young men in my own locality who are unable to read the registration number on their boat, or write the name of their Canadian product upon their lobster crates bound for the U.S. But now, through organization we have study clubs started, and children and parents are learning to read and write – one of God’s greatest blessings. And we are looking for books and libraries too, because we have learned to value such things. The adult education movement, started by the men of St. F.X., has produced more than one thousand study groups in eastern Nova Scotia alone and the university rolls show more than 30,000 adult members.

The Whitehead Co-operative Society was incorporated and packing its own lobsters, shipping them via the U.M.F. in Halifax. It was involved in processing, producing salted and boned fish and cod oil and it had its own ice house and grocery sotre. The Halifax papers were covering co-op news regularly. Special periodicals had sprung up such as the Canadian Co-operator and the Maritime Co-operator. The merchants and business men were continuing to throw all kinds of obstacles in the part of co-operation, dragging in politics, religion and anything else that came to hand. But a solid interaction had sprung up between the coastal villages:

Over in Port Felix, and previous to our organization there was a line fence, so to speak, between us, and each fellow kept on his own side of it, Protestant on one side and Catholic on the other. We had no business transactions in any way. Since we fishermen began to organize and co-operate, we have become fast friends. Today that little fishing locality of Port Felix boasts of as fine a store as in most fishing villages and it is owned and run by the fishermen themselves. They also own a co-operative lobster factory. I am proud to tell you that there are twenty-two shareholders from my own locality who have an interest in that factory.

So spoke and wrote Billy Tom. His articles appeared throughout Canada and he wrote a pamphlet for St. F.X. called “What Fishermen Are Doing.” Sponsored by the Canadian Association for Adult Education, he spoke on CBC-Radio from Halifax and the mail poured in from across Canada and the eastern seaboard of the United States: people asking for copies of the talks, offering their help, their ideas, or storied of their own co-operative adventures. The Associated Co-op Study Clubs of Boston built a playlet around the “Fifty-Cent Year” incident. The I.O.D.E. asked to publish his speech entitled “With Thy Help and My Help”. The N.S. Economic Council asked for copies of his words. Parliamentary groups, particularly the C.C.F., asked for advice and information as did both the Co-operative Research Bureau of Canada, and the Canadian International Centre of Research and Information of Public and Co-operative Economy, in Montreal. The Halifax newspapers and the Maritime Co-operator asked for a series of articles. He spoke at the Sea Fisheries Conference in 1938 and was asked to assist with a special broadcast done for the B.B.C. The Co-operative League of the U.S. toured Nova Scotia and published the Whitehead story; and perhaps most exciting of all, TIME of New York sent a film crew to Whitehead to make a March of Time newsreel that was released internationally in 1940. Meanwhile the local meetings and the St. F.X. courses continued.

In January 1941, Billy Tom turned 65. In June of that year, Father Jimmy, aged 71, was one of 12, and the only Canadian, to receive an honorary degree at Harvard University, for his work in the Antigonish Movment. Up in Cape Breton, he had managed another miracle: spear-heading a whole regional library system for Nova Scotia.

The war had taken the focus off the co-op movement. But there is no doubt that the previous decade had brought about a complete change of attitude among the people, a different mentality, a new vision of the future. Twelve years later in 1953, the centennial year of St. F.X., Father Jimmy died. In 1959, Dr Moses M. Coady and Billy Tom Feltmate died. In that same year, the Coady International Institute was founded, designed to foster self-help and co-operation beyond Canada, training leaders at a grass-roots level all over the world. Since then, the Institute has trained more than 2,000 people from 100 countries [as of 1980].

Today [1980] we may read that Canada’s finance minister Allan MacEachen credits Dr. Coady with being a major influence on him; or that a new branch of Nova Scotia’s regional library system has been opened as a Tompkins/Coady memorial; or that Godfrey Chakabuda of Rhodesia says the Antigonish Movement is known throughout the world.

And what of the Blue Ribbon Canners in Dover ? In 1975 they invested in a boat building and repair facility. Three years later they bought a sawmill. And now they boast the best marine slipway between Port Hawkesbury and Halifax and probably produce more inshore boats than any other manufacturing company in the province!

But Billy Tom sums it up best:

The story of how I fought through the Depression is not my story alone. It is the story of hundreds of fishermen along the coast who fought through as I did and who fought through with me. At least – we’re part way through; we’ve got a long way to go yet…

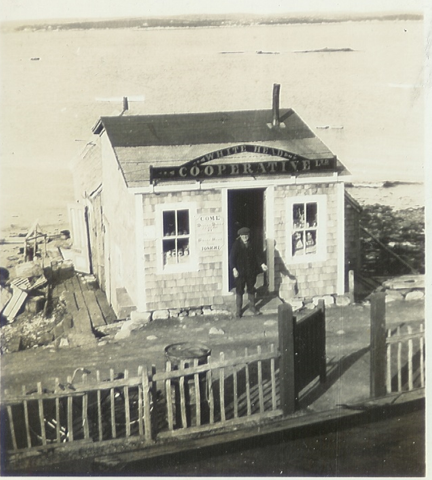

Two shots of Billy Tom Feltmate in front of the first little Whitehead Co-operative store, which was on the shore of White Head Harbour directly across the road from Billy Tom’s home. Above right, Billy Tom is on the right, talking with a fisheries consultant Roy Churchill.